Storytelling Tools

Storytelling Tools to Boost Your Indie Game’s Narrative and Gameplay

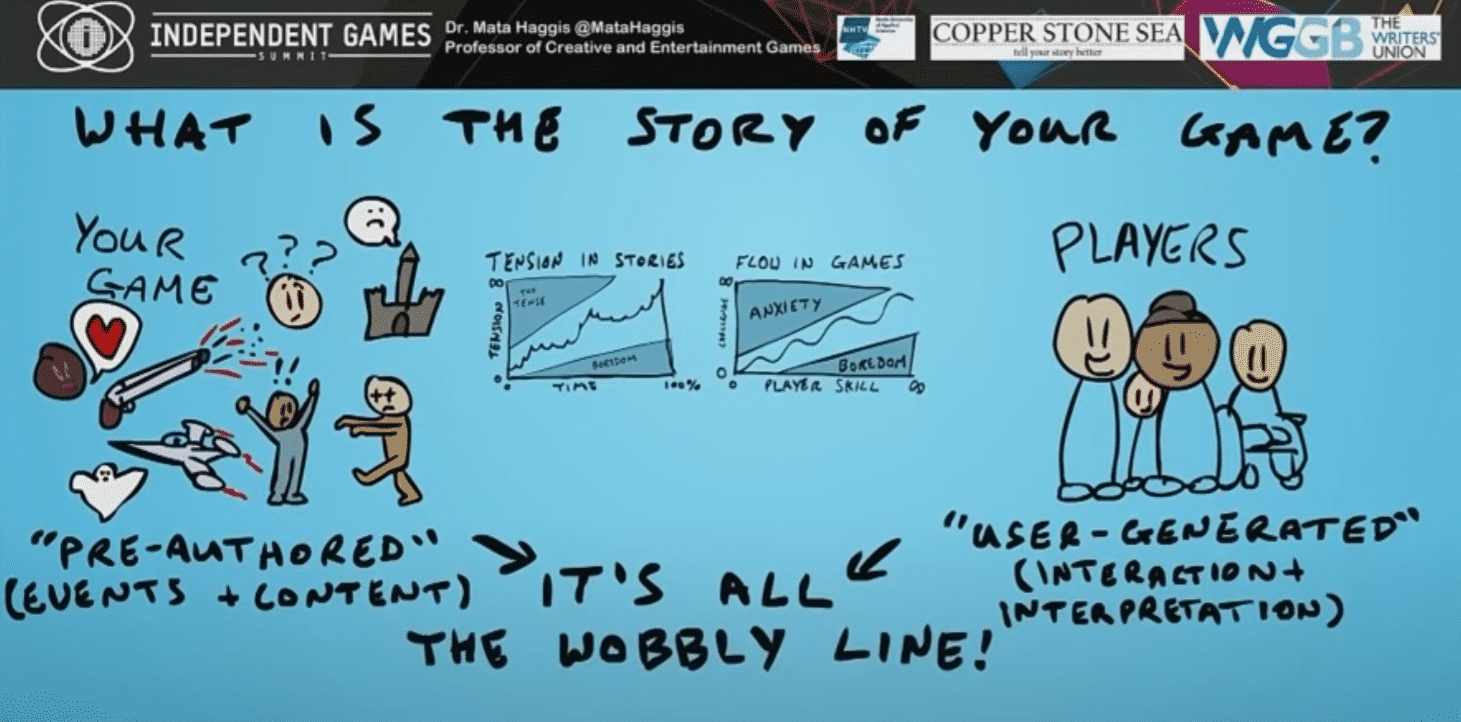

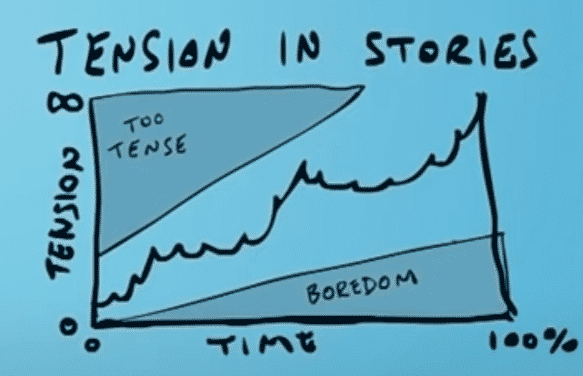

Storytelling Tension and Flow

Basics of Storytelling

- Internal & External Motivation

Intrinsic & Extrinsic Motivation

External motivation is the desire to change something in the world outside

- Richer, Travel

- Internal motivation

- Usually overcome a problem (emotional)

Plot Structure

- The Character has their goal

- Need a well-structured series of events through which change will happen

- The plot controls the speed of progress of the tension arc in the experience

Start before your big event begin

- You Don’t start your story with (you are a wizard Harry)

- Set up the character, the situation, and the basic rules

- This is otherwise known as ‘the tutorial mission’

- It is important to build Empathy

- We must want the character to overcome the challenges ahead

- Before we reach the lake in Firewatch, we know a lot about Henry’s life (setting up his external and internal objectives)

The inciting Incident

- Now your player knows their place in the world, we can start to set up the challenges

- Increase the narrative or mechanical tension

- Add an antagonist/enemies, risk, or a break in the usual situation

- Overcoming this problem is usually the external motivation of your plot

The player avoids the problem

- The player usually does not go straight for attacking the problem

- They either explore, avoid, or attempt smaller battles

They make a choice to act with intention

- After a while, the player feels they know enough of the territory to make a focused choice to act

- Or there is no choice left but to act.

- e.g. “I’d better use the map more”

- They engage with the external objective of the game/story

The complexity increases

- The basic abilities seem less effective, new enemies are added, new story elements show that things were not so simple…

- Tetris is a masterpiece because of the complexities is in the gameplay, the complexity is changed by player’s choice. Storytelling moment.

- (Narrative, mechanical, or both).

Example

- In Virginia we see divisions between the protagonists, and dreams call reality into question

- In Firewatch an extra layer of conspiracy is added

- In Fragments of Him, Will doubts if he can sustain a relationship without hurting others.

Complexity raises the stakes

- The first strategies and weapons are no longer enough

- In shooters, new patterns and combinations of enemies are added

- Enemies use better targeting, more bullets, or homing missles

- Enemies get dangerous new abilities

Hope overcomes fear … With effort

- The player finds new weapons or strategies to overcome the enemies (external change, e.g. power-ups or grinding)

- They find strength they never knew they had (Internal change)

- They character learns to unite their skills/team behind a purpose

- It has high risks, but it’s the only hope

‘The Black Moment’

- All the hopes of overcoming the problems are at risk

- The final boss is killed … But this is not even the final form

- All the knowledge, the relationships, and the strategies developed through the player/character’s experience are needed to overcome this final challenge

And then you end it as fast as possible

- Keep the ending neat and short

Basics of Storytelling

Tha’t’s a model for most stories

- As a player/character journey, it fits most strong experiences

- This works on an intuitive and emotional level to feel rewarding

- But…

Making a thriller, action, or a horror story?

- There’s an additional bit of the structure you might want to consider adding

- ‘The grabber’ is a burst of action or fear at the beginning that promises the future of the game before it slows down for the ‘before the inciting incident’ scene building

- It’s a way to let the player know that there is exciting moment ahead

- In horror stories, you also often have a final moment of fear at the end (Evil lurks)

- But you also sometimes have this for thrillers, where the defeated organization has actually survived or the war was bigger than the one battle we’ve seen.

Scene structure

- All scenes or levels of your game must have:

- an objective (a target player goal or experience)

- ‘conflict’ (something that makes the objective more difficult to reach: narrative/mechanics/both)

- an outcome is then reached by requiring change from the player

- They either resolve or adapt to the conflict, building to the next part of the experience

Narrative example: Aliens versus Predator

- Objective - reset power to get the colony working

- Conflict - the player successfully resets the power, but it blows circuits across the colony

- Outcome - The colony is more at risk than before and the character’s life is more complex

Another example: Mechanics: God of War

- Objective - continue killing everything

- Conflict - enemies with shields block the usual attacks

- Outcome - the player needs to use new attacks to progress, making the game more challenging - complexity increases for the player

Games are players’ stories

- If your game feels flat, then thinking of your player’s experience as a story

- Here are four debug questions to ask if a game, event, or level feels unsatisfying:

- Is the player’s objective clear?

- Is there escalating mechanical or narrative conflict, or is it only repetition?

- Does the outcome meaningfully add to the mechanics, narrative, or both?

- Over the level or the game was there change from the start to the finish, for the player, the character or both?

Conclusion

- Good designers already intuitively use story structures to create compelling and rewarding games

- Learning to do it consciously is a powerful way of understanding how we shape the great experiences

- Whether your game is narrative or mechanics oriented, learning to think like a storyteller helps you make intelligent player-focused design choices